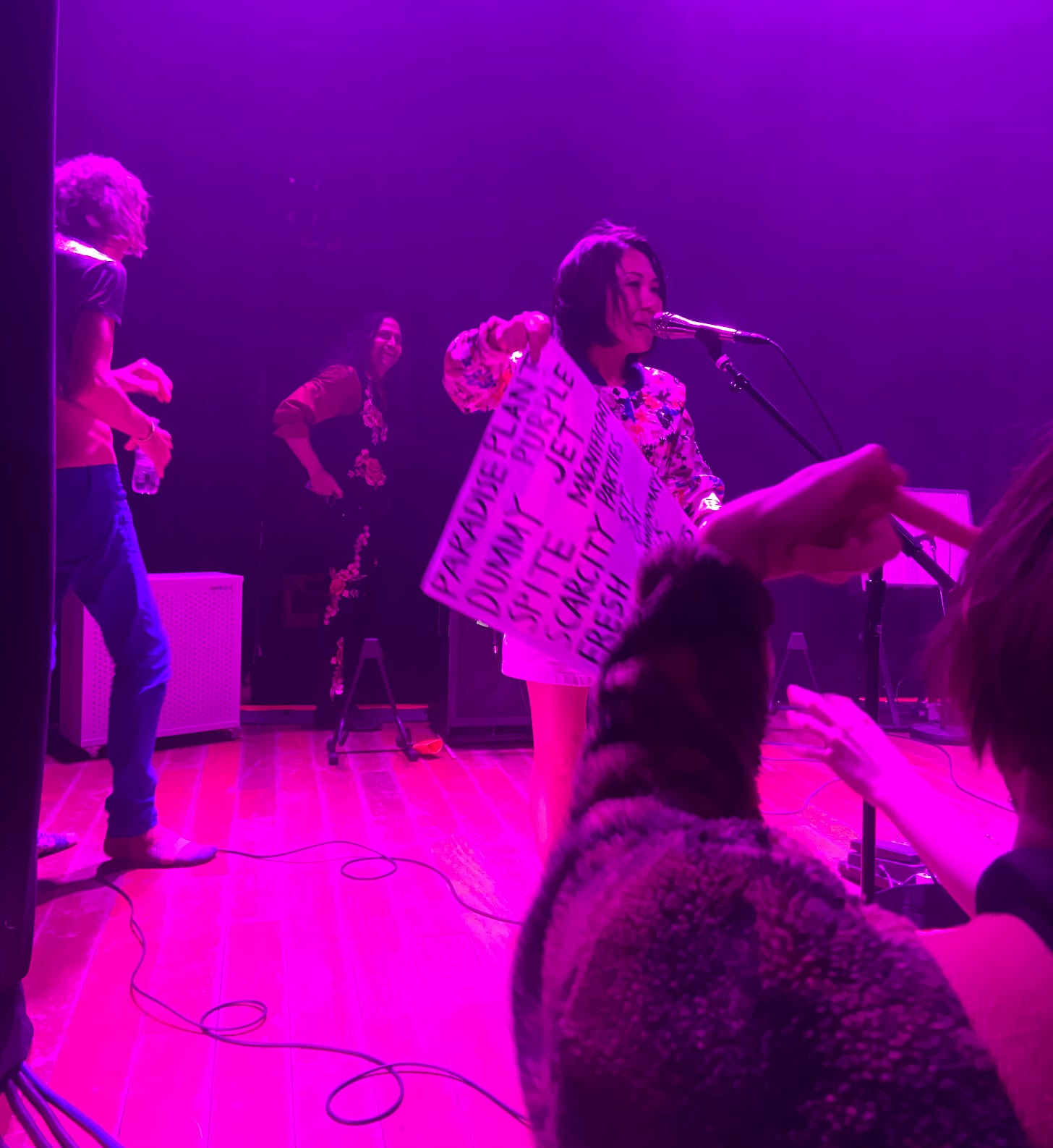

I dialed the number and anxiously waited for the phone’s ringing to stop. When it did, I thanked Greg Saunier, founder, for taking my call after the band had returned home from a demanding tour. Today Deerhoof consists of drums and vocals (Saunier), bass and vocals (Satomi Matsuzaki), and two guitars (John Dieterich and Ed Rodriguez). Just the night before, I was at their last show at Lincoln Hall. Afterwards I was still raving over the performance and their latest album, Miracle-Level, which I had repeatedly played through my headphones on my daily adventures around the city. It became the soundtrack of the burgeoning spring season along with the sounds of Sonic Youth, Radiohead, Tortoise, Liz Phair and other experimental, guitar-centered favorites of mine. Lincoln Hall was filled with many different kinds of people with a common, shared appreciation. The opener welcomed us with their psychedelic riffs and sensitive lyrics which Saunier complimented once Deerhoof took the stage. The band showed genuine chemistry, and they interacted with the audience as if there were no platform separating us. We felt intimately connected by the emotive sound filling up the entire venue, and their playful and sincere adlibs between songs created more closeness. After a gracious encore, no one wanted to leave the venue, and I became more eager to conduct the over-the-phone interview the next night. Saunier and I conversed for over an hour-and-a-half, and I could not be happier with what came of it. A college radio interview quickly became a deep reflection on creativity, productivity, and the healing properties of music that informs my own artistry from now on.

Around 30 years ago on April 8th, the same date of the interview, the band met to rehearse for the first time. I asked Saunier to reflect on what he called their “inauspicious” beginnings which took place after college in San Francisco, California. Saunier had studied music composition and was interested in entering the field of ethnomusicology. Their sound was underground and grungy, inspired by a British group, AMM, whose approach was strictly improvisational. Saunier was also deeply moved by the loss of Kurt Cobain of Nirvana at the time.

“Everybody forgot that guitars even exist and everything became really, you know, techno … it just felt like, wow, our timing was really bad … how many years did Deerhoof go from that point forward before we ever made any money at all,” said Saunier.

Then, the band was somewhat unplanned and seemingly unpromising. But the group’s love for the craft compelled them to keep playing. So they did. Soon after came Satomi, the lead vocalist who was instrumental to the dynamic from then on. Through friends of friends, they were introduced and she casually came to hear them play in their kitchen with no prior experience. This was all within a week of her move from her home in Tokyo, Japan to California, USA.

Saunier called it an “absolute trial by fire.”

“She was thrust into this incredibly bizarre, total culture shock, very chaotic and somewhat broken music situation … it did not phase her at all, there was no look of fear on her face … and for me it was like fifteen seconds of playing together and I just knew.”

He believes that the formation of Deerhoof did not happen solely by chance. They also needed to trust their intuition that the music they were making meant something, even if only to them.

According to Saunier, the inner dynamic of the band is not as simple as perfectly sized puzzle pieces fitting together. Their unconventional creative process involves intertwining four unique individuals.

“We don’t listen to the same music and we don’t have the same taste,” Saunier said.

“It’s much more common that somebody has sat at home in isolation and written an entire song by themself, you know, quietly in the corner with no one listening. And then they feel really nervous and shy to bring it to the band because they know that the band is probably going to think that it’s really weird … we try and figure it out really gradually.”

The band’s decision to write the album Miracle-Level in Japanese was inspired by current singers in pop culture like Rosalia who are not compromising their linguistic preferences in order to prioritize English. This choice directly impacted Satomi’s role on the album.

“I felt more that she was the powerful element in the chemistry of it,” Saunier said. “Her role became more powerful, more commanding, more emotional, more direct. Nothing felt like it was being translated. She was singing her own poetry in her native language … The rest of us were the ones who were being asked to do something that she had to do for so many years … we had to make the adjustment and we had to figure out what to do when we don’t totally understand what the singer is singing about.”

In a way, it was an experiment. And all of Saunier’s music-making process is experimental.

“I still completely feel like a student myself and a beginner and everything I try is an experiment,” Saunier said. “I don’t know how it’s going to turn out. The first step is to try it.”

Deerhoof has put out 17 studio albums since 1997. Saunier’s approach to music making starts with a notebook where he documents countless ideas.

“I know for myself, I’ll go through my notebook and there’s just zillions of melodies, rhythms and all kinds of ideas in there, and I’ll probably use like two percent of it, you know. Two percent of it ever ends up in a Deerhoof song, or something. The other ninety-eight percent, I’m like why did I ever write this? … It ends up being better to just put it down. And then, before you know it, the idea might be pulling you along and you don’t have to worry about it.”

Issues of self-consciousness or self-doubt stop many of us from making art, but there are even larger, more systemic forces threatening our creativity that we could not leave out of our conversation. Saunier was unafraid to voice the difficulties of the music industry.

“We’ve been so trained to think of music as a business and as content, and we’ve been so trained to judge our content based on a popularity contest,” Saunier said. “It makes music-making become a competitive human behavior.”

So, if the monetization of art and music is all-encompassing, what control do artists have?

Saunier said “it can be hard not to get demoralized and feel like if you don’t hit the jackpot right away then you aren’t being validated. But that’s why a community and friendship is really important…it’s key.”

The concept of an artistic community was not obvious for Saunier in the beginning.

“I was a very isolated kind of person who was not a part of the music scene. I just thought it was all about planning every move in my mind and making it very perfectionistic… It took several years for me to start to understand that the only reason this is any fun at all is because there are other people around who feel sort of similar feelings that I feel. And I don’t feel like an alien as much anymore … at least give each other a space, a platform, a turn at the microphone.”

He felt that these spaces, where everyone gets a turn at the mic, cannot thrive under the pressure to accommodate the industry. In his eyes, the over-monetization of art is part of the deeper issue of capitalism.

“It’s part of the colonial project, forcing this competitive doggy-dog philosophy of existence onto every aspect of life. Including the arts and including music. And if your music doesn’t have certain features then that means it’s savage, that means it’s barbarian music or it’s not civilized.”

I prompted Saunier to talk more about hustle culture and hyper productivity in relation to creativity.

“It’s almost like a fairytale, if you work really really hard, you’ll be rewarded. Of course that’s a lie, it’s not true. There’s so many other factors. What amount of money are you starting off with? What is your gender? What is your race? Where do you live? How much trauma are you growing up with? Do you ever get a break from that trauma and do you ever recover? What’s your health situation? … The list goes on … I think that when Deerhoof started I had fully swallowed that indoctrination. And I did feel that there was inherent value in being prolific.”

We continued reflecting on the ways artists are made to believe our worth and validity are measurable by how much work we produce during our limited lifetimes and how many accolades we win.

“It’s amazing how few successful musicians really appear to be all that happy. They seem more stressed out than anybody,” Saunier said.

“I’ve known bands personally … They’ve now got an army of managers telling them to stop putting out records because there’s no way you’re going to get a ten on the next … Music was the one thing in this world that they loved, that they were passionate about, and that they were good at. Now they’re being instructed to stop making music or else it’s gonna destroy their career. I’m so glad that we’ve never reached that level of success. That just sounds like absolute torture … I like being creative everyday. And that, for me, is the practice. That is the joy of it.”

Over the course of their expansive career, the band has luckily been able to maintain a sense of authenticity and healthy creativity despite external pressures.

“I feel that Deerhoof has for a long time now been really in the sweet spot where we can get away with putting out a lot of things because we don’t have to have a million fans. It’s enough to have a few thousand fans … This idea of enough, it’s like, in our capitalist world nobody has ever heard of the word enough. In fact, enough is not allowed. I mean, that isn’t capitalist. Capitalism means infinite growth. It means you always have to be earning more or getting more capital or else that’s counted as a failure … the burnout is real.”

Joyful Noise Radio Hour conducted an interview with Deerhoof in 2022 in which Saunier recalled a stressful period during the pandemic. Making music was necessary to withstand this intense time. For him, it was an opportunity to reflect, heal, and be creative.

“We were watching the planet heal itself because people were not working, in fact, we’re all working way too much, too hard … There’s too much extraction of resources. And like you said, there’s too much burn out. Humanity is suffering and the climate is suffering and becoming inhabitable … It was in lockdown that I realized, for me, doing the musical work was actually not, it didn’t have anything to do with a work ethic, and everything to do with how much stress I was feeling and this was a coping mechanism for me.”

Wide-spread chaos during the pandemic pulled out of Saunier a need to cope, and Deerhoof was a kind of therapy.

“We are not churning out content for the sake of churning out content, we’re like struggling to figure out what is our purpose on this planet and how does anything make sense. Last night in Lincoln Hall there were several times … we’re in the act of playing our songs … and I find myself trying to access deep emotion, and a lot of times it’s grief … there are times that I weep when we’re playing.”

We segued into Saunier’s latest release, We Sang, Therefore We Were, an exploration of music’s ability to engage all our senses and help us process complex things. The album is an exercise in interconnectedness in response to an often disconnected society.

“I don’t feel the separation between my head, my body, and my heart. The experience of playing music is intellectual, it involves thought … but it also involves the emotion and it also involves the body … it’s an integrated full human experience … that’s how it actually feels to me when I’m playing a show.”

Since the conversation, I continue thinking about art, finding community in the Chicago music scene, and the healing that can take place when creativity is allowed to thrive, exemplified in Deerhoof’s expansive career.

I also think about how I can reconnect and reach my own “miracle-level” by practicing free creativity and validating all corners of myself to become a more whole individual and thus a more whole artist.

Endless thanks to Shane at Audiotree and Aden Van Hollander at Radio Depaul for your help in making the interview happen and to Greg Saunier for your vulnerability and openness during our call.