As a student reporter in the journalism department, television, newspapers, and radio have been essential sources to use and report with. It’s a source that allows many of us to connect and find similarities in what we like, dislike, agree, and disagree on. Yet, there are some over the years who have looked at it as a dangerous thing. Something that is invading our privacy and that needs to be rid of. Even as we face those battles today, I want to share how this has affected society and how it may affect you through this series.

The Beginning

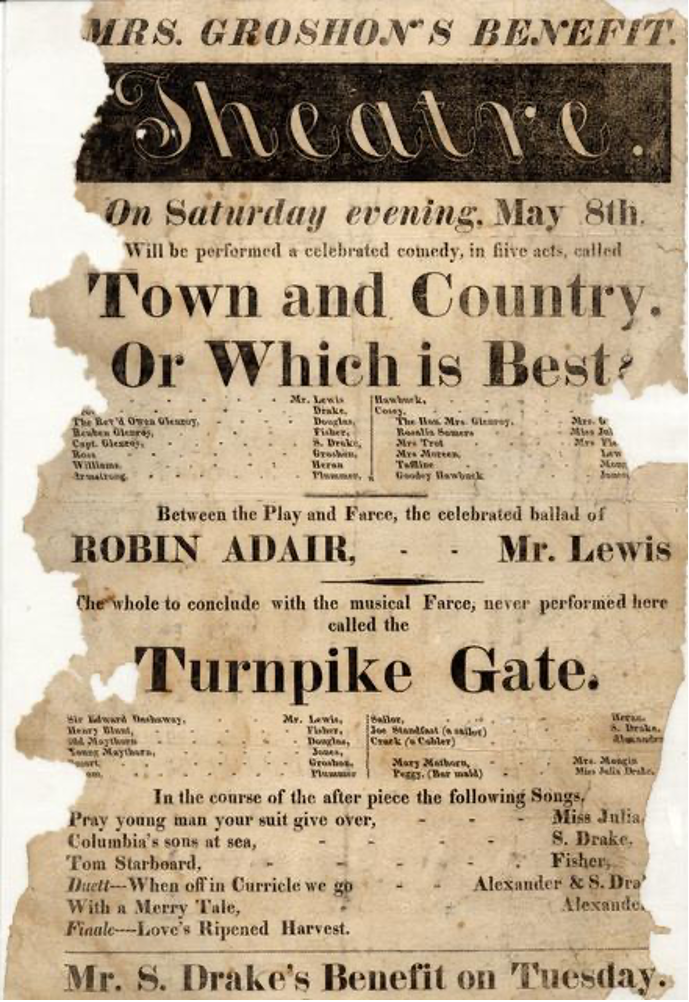

What we know now as newspapers started in a minor form called a Broadside. A Broadside would contain only a page’s worth of information; it could contain advertisements and other news. These types were intended to be viewed and thrown away (Library of Congress).

However, most stories reported on Broadsides would not last in the light of today’s society. Many Broadsides would illustrate photos of crimes, portraits of the criminal, written accounts of the crime, the trial, and confession of guilt. It would also include a part of the hanging if that was the sentence (Harvard Law Today).

Broadsides weren’t as notable in the United States as in the United Kingdom. Did this mean that media coverage was going to end there? Of course not.

One American by the name of Richard Pierce and Benjamin Harris from England attempted the first and only one of its time, a free press. With only one copy of it still in existence, it lays down our history of the news, but news that others didn’t like (Poynter). The title, “The Publick Occurrences,” consisted of four pages with two columns, with the last page left blank, which allowed a letter to be written for a family or a friend.

The issue was published on Thursday, September 25, 1960; it had an account of a battle waged by General Fitz-John Winthrop during the French and Indian Wars covering the brutal treatment of French prisoners of war. Other sections included information about the smallpox outbreak and a story about the king of France, Louis XIV, who supposedly slept with his son’s wife. The coverage of the war story angered the Colonial government, and in doing so, they ordered an immediate suspension of the paper. Four days later, it was (History of Information).

The Aftermath

While Broadsides continued publishing until the 19th century (Rare Americana), it pushed Richard Pierce to make his only notable free press paper, “The Publick Occurrences.” It may not have lasted as long as he thought, but it was a more in-depth published piece than Broadsides was.

Yet, many began to fear what would happen if they wanted a “free press,” would it be allowed? Especially after the Colonial government had taken down Pierce’s so-called pamphlet’s aftermath work. But if everyone had feared this, the news outlets we know now of today’s history wouldn’t be shared. Luckily, in the early 17th century, a governor allowed for the publication of the Boston News-Letter (Massachusetts Historical). This would lead to others down the road starting publications.

Although the British government had monitored the Boston News Letter, there was once again a publication that was available for the public to read. Although the work published mainly in the newsletter wasn’t what the people wanted to hear, it was what the government wanted to be heard.

Photo: Library of Congress