Justin Chon’s fervid third feature, “Blue Bayou” (2021) walks the line between a meaningful drama and an overly melodramatic film with a kick in the gut that will reignite your sense of humanity.

Chon’s blunt message criticizes the cruel and dehumanizing American immigration system by attempting to reach into the innermost part of the audience’s hearts. “Blue Bayou” follows the story of Antonio LeBlanc (Justin Chon), a Korean-born, American adoptee facing deportation after living in the United States for over thirty years.

“You’re going to realize that they are a mother or father, and have their hopes and dreams and worries. We’re all human,” said Chon in an interview with Rogerebert.com.

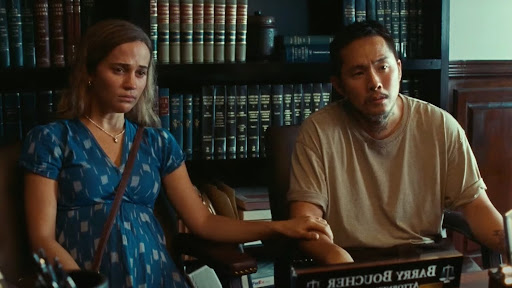

Antonio lives in the New Orleans area in Louisiana with his pregnant wife, Kathy (Alicia Vikander), and his step-daughter, Jessie (Sydney Kowalske). He doesn’t have much but fervently attempts to create a better life for his family. His family pulled him out of vast childhood trauma and criminal past.

When the audience meets him, Antonio lives a grounded and honest life, working at a tattoo parlor — but yearning for something more prosperous for his family. Antonio is comfortable in his American identity. Jessie is Antonio’s step-daughter who he loves and cares for dearly. To Antonio, blood and genetics are not what defines family, rather love and choosing those you love, regardless of biological relation.

“Blue Bayou” visualizes the horrendous effects of an exploitative and broken immigration. This film critiques the system by showing how unnecessary it is to rip apart families and create trauma for children, all because of misfiled paperwork. The system deports people who add to society, have friends, families, and communities in America. Chon displays the real, irreparable gravity of the actions of the US government.

The word “choose” is a seminal word throughout the film, as Antonio wasn’t chosen by his biological mother and numerous foster families thereafter. However, he chose Kathy and Jessie, and they chose him.

Ace (Mark O’Brien), a New Orleans police officer, is Kathy’s ex and Jessie’s biological father, whom he abandoned but now regrets. At first, Ace seems like the antagonist, but soon we realize that Ace is not the one to hate, but rather, his racist and dangerous beat partner, Denny (Emory Cohen). Denny arrests Antonio under false pretenses and initiates the entire deportation debacle.

During Antonio’s deportation legal battle, he meets a Vietnamese-American woman named dying from cancer who comforts and advises Antonio during this strenuous time, acting as a sort of spiritual advisor. She guides Antonio’s aching soul as he confronts, and eventually accepts, the suppressed Korean identity that he buried away many years ago. By the end, Antonio is no longer afraid of his traumatic past. He is not fully healed, but is at ease with both his past and present selves.

The film is a saga of intergenerational traumas that seep into your future and are difficult to outrun — the kind of trauma that transfers past pain into future loved ones and will continue to transfer if not addressed and extinguished.

Chon’s beautifully filmed and breathtakingly haunting visual composition will transport your consciousness into a scary, yet enticing, dreamworld. The setting of Louisiana itself is a character and will make your heart yearn to witness its underrated beauty in person. Rarely in films, do we see the South’s nature, sky and setting filmed in such an enchanting and romantic manner.

Chon’s cinematography in New Orleans leaves a melancholic taste in your mouth. It shows a beautiful side of New Orleans many outsiders never see, but the story’s sadness wraps that beauty.

“Blue Bayou” is a saga of intergenerational traumas that seep into your future and are difficult to outrun — the kind of trauma that transfers past pain into future loved ones and will continue to transfer if not addressed and extinguished.

The color composition is utterly mesmerizing: The vibrant and saturated cool colors in the film set the melancholic mood throughout the entire picture. The cinematography uses a distinct style that you will remember for years to come. The cinematographer’s use of natural lighting, saturation of colors, stylized shot composition and utilization of the 16mm film grain are some of the most memorable shots I’ve seen in a while.

The soundtrack beautifully enhances and maintains the mood and tone of the picture with its orchestral ballads and emotional music.

Chon’s melodrama may be over-the-top at certain points, but it doesn’t take away from his ultimate message. For instance, in the last scene of the film, Antonio is forced to leave his family behind in the States. The writing borders on overdramatic, but is carried by powerful performances from the actors.

Oftentimes, dramatic films create a void between the audience by needlessly over-exaggerating or creating circumstances of exploiting a subject matter for a greater emotional response. In “Blue Bayou,” Chon successfully toes that line, although the writing is over-exaggerated and unrealistic at times. It personalizes the family’s struggle. The film reminds the audience that families are broken and children traumatized every day by showing real people’s deportation stories.

Chon’s directorial vision displays that he is on his track to fully realize his artistic style and voice, and it is clear that he will only get better.

“Blue Bayou” will leave you heartbroken, irate, and compelled to take action to end the cruelties and suffering of deportation.